Let's be civil about this

Social media bans for children are the great moral debate of our time

On a bus in Sydney a couple of months ago, my husband and I sat behind a group of boys on their way to the beach.

I’d say they were 12 going on 13, that age where some still seemed like children and the others like teenagers. As we wound through the suburbs, they alternated between raucous conversation and getting lost in their individual screens, watching podcast clips and short videos about sharks.

Even when they were talking to each other, their Australian accents often disappeared as they imitated something they had seen, snippets of American speech. One phrase seemed a particular favourite: “Gentlemen, gentlemen, gentlemen, let’s be civil about this.”

There was something about the way they were trying to sound like characters in a movie as they said it. I assumed it must have been a line from The Wolf of Wall Street or The Big Short, cut up and meme-ified.

But when we looked it up later, it transpired that it was not from anything. It was a sound that seemed like a quote from TV or film, but had in fact been made up by musician Naethan Apollo when he was just goofing around on TikTok.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

This was both funny and, to me, a little unnerving. These kids were swimming around in a kind of post-culture culture. Nothing had any context. Did they still have favourite books, albums, films, or were they content with whatever the perpetual stew of the algorithm gave them that day?

There are a lot of reasons to be worried about how children use social media. From threats to their personal safety and exposure to explicit content, to the impact on mental health and the loss of time and attention span.

But there’s also sometimes a strain of reactions like mine. People who see in the behaviour of young people a future hurtling towards them that doesn’t value the things they hold dear. It’s a familiar feeling of generational shift that we all know from history is inevitable, yet we are still surprised when we become the disapproving older cohort.

Sometimes this is mixed with a sense that we, the adults, have already been corrupted, and if we can’t save ourselves, maybe we can save the children.

The question is whether they need saving.

As the bus reached their stop, the boys put their phones away and disembarked, debating whether to have a swim first or go fishing.

By this time next week, those boys should in theory be unable to use TikTok at all – or indeed Threads, Facebook, Reddit or even YouTube. Under the Australian amendment set to come into force on 10 December, social media companies must ensure under-16s do not have accounts on their platforms or face fines.

While it will only apply in Australia, the change has proven a rallying point for those who would like to see similar rules put in place in many other countries, including here the UK.

Of course, Britain already has the groundwork for such a ban in the form of the Online Safety Act, which requires age verification anywhere there might be adults-only content.

But this shows no signs of having obviated the demand for stronger action. There are several petitions online with thousands of signatures calling for a ban on under-16s using social media, one of which prompted a debate in Parliament back in February. At that debate, Chris Bryant, who was data and telecoms minister at the time, said: “I would be amazed if there were not further legislation, in some shape or other, in this field in the next two or three years.”

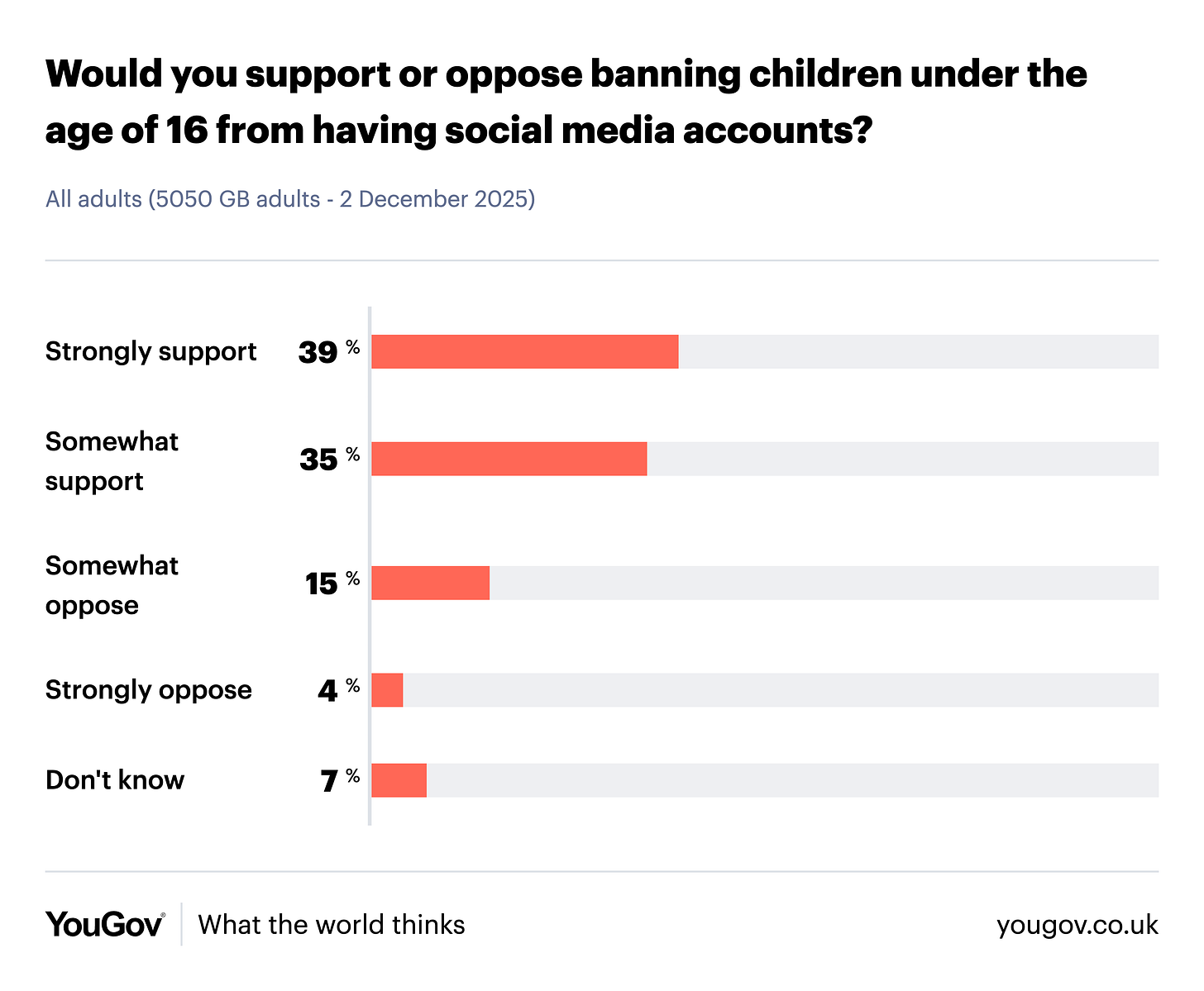

Off the back of Australia’s ban, YouGov polled the British public this week and found that three quarters would either strongly or somewhat support raising the minimum age for social media usage.

This is a tough one for policymakers to approach because it appears to combine consensus opinion on the problem with disparate ideas about the solution.

I would argue that this is in part because the consensus is not as united as it may seem. One might agree with the general desire to get children spending less time online, but what is the primary motivation for that? Is it fear that they’ll be exploited or cyberbullied? Is it to limit their exposure to an addictive algorithm so they don’t get a taste for it too long? Is it out of fear that scrolling will further displace reading and sports? Is it to keep them away from Andrew Tate?

The answer might be all of the above, and many more besides. But it’s crucial for a workable solution that anyone calling for a ban has a clear idea about what effect they want it to have and what the unintended consequences could be.

Already, the Australian ban has come in for criticism that it will just move teenage interactions to Whatsapp, Discord and other private messaging services. As the UK already found with the OSA, these measures can also be controversial because they affect the online lives of adults too and verification brings a slew of privacy concerns.

Meanwhile, the changes already look a step behind given that they don’t address a newer trend: teenagers increasingly turning to AI chatbots for social interaction.

Making sense of this issue is a defining debate of our times. It touches on fundamental questions about liberty, safety, quality of life, culture and education.

And as I alluded to earlier, the discussion also often betrays something about how adults might be questioning their own relationship with the internet and smartphones, and projecting those fears onto a group whose lives can be more easily circumscribed.

One final note that I found interesting when looking into Australia’s move: it’s been reported that it originated when the South Australia Premier’s wife read Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation.

That same book has been instrumental in efforts across US states to limit the use of phones in schools. Haidt has welcomed some of the legislation that linked to his work, but he has always argued that this is a collective action problem: society as a whole has to take part in shifting the norms around smartphones, he argues. This is a problem so complex that it can’t be resolved by laws alone.

Teatime scroll Each week I share links to writings, events, tweets and other conversation-starters. If you have something you think should be in here, feel free to email or DM me.

🖱️ Cursor users are invited to swing by next Wednesday when the team is taking over a café for the day in London.

🏢 CRM startup Attio, which is backed by Google Ventures, is taking on a new London headquarters.

🧾 An email from Anthropic prompts Oliver Ritchie to argue that AI systems should pay taxes in the same jurisdiction where they have replaced humans.

🚗 Over on London Centric, there’s a useful analysis of what went wrong for Zipcar in London. My question is whether those affected are likely to get their own cars, switch to Ubers and hire bikes, or become customers of Wayve and Waymo.

📊 The Observer has just published its Global AI Index, ranking the UK at number four. But it’s a familiar analysis of the ways Britain is failing to capitalise on its position: lack of growth capital, talent going elsewhere, infrastructure.

✉️ Some professional news: I’m now doing some part-time work with the Centre for British Progress as Editor. They’ve been up to some cool stuff recently – if you haven’t seen the Nuclear Taskforce Tracker yet, you’re missing out. You can catch some of my work over on The Progress Post.