The creative destruction problem

Breaking free from stagnation requires a hand on the wheel

A brief one today, plus an extra-long links section, while I work on a couple of longer pieces for the coming weeks.

This week, Nobel Prize honorees arrived in Stockholm to receive their awards. Among them was a trio of economists: Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt. All of them, as Mokyr acknowledged in his speech at the Nobel banquet, owe a debt to the Austrian economist Joseph A. Schumpeter, who was first to propose the idea of “creative destruction”.

This catchy oxymoron is a way of describing the process through which progress is achieved: out with the old and in with the new. New knowledge and inventions disrupt incumbents, leading to the destruction of old industries and jobs, but equilibrium is (hopefully) maintained when these same innovations create new opportunities. Often ones that might have been inconceivable in the past.

But the process, Mokyr explained, is not painless. Creative destruction “can eliminate jobs, devalue human capital and capabilities, enrich the rich and impoverish the poor, and cause unprecedented environmental degradation”.

He acknowledged that these are legitimate fears, but argued that innovation is the only way to solve humanity’s most pressing problems, “because any alternative will be disastrous”.

Creative destruction, as the FT’s Tej Parikh pointed out earlier this year, faces preservationism at every turn: from those who want to limit its damage, those who don’t want new houses in their area, those who want to maintain their dominance over markets, countries that want to protect their industries. If anything, it’s the most understandable human impulse played out on a grand scale; we like to keep things safe, keep them the same.

The cost of that, though, is stagnation. Earlier this week, the ONS released its latest figures tracing business dynamism in the UK.

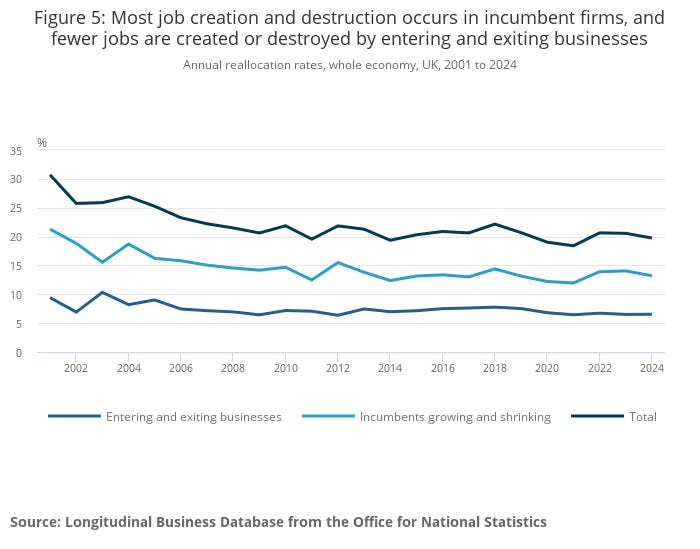

The job reallocation rate, which measures job creation and destruction as a proportion of totally employment in a given year, gives an insight into how dynamic the labour market is. In 2024, the rate declined slightly to 19.8%. This rate has remained relatively stable since the financial crisis, without showing much sign of reaching pre-crash levels.

Meanwhile, business exit rates exceeded entry rates for two consecutive years (2023-2024), meaning businesses are leaving the market faster than innovative new firms are entering, a bad sign for the fine balance of creative destruction. At the same time, the productivity gap persists, with workers at the 90th percentile now producing 3.5 times more output than median firms. In theory, competitive pressure should reallocate resources from less to more productive firms, but this doesn’t always seem to be happening.

The huge, unanswered question is whether AI can deliver a productive form of creative destruction that revitalises slowing economies like ours, or whether it will only succeed in causing destruction of livelihoods and institutions (the graduate jobs problem being an example of both) while its benefits are distributed unevenly.

In their lectures, all three Nobel laureates acknowledged some of the downsides of unbridled creative destruction. They also spoke of it not as a purely natural force, but as something that needs coaxing.

Peter Howitt noted that competition policy, for example, has a crucial role to play in ensuring incumbents don’t end up quashing innovation and gumming up the works of the creative destruction process, whether by buying up rivals or through the delightfully named “patent thickets”.

All this suggests that it’s not a case of sitting back and letting these natural economic forces roll through and see what happens. That gesture of powerlessness is something we see too often across AI in general, and it undervalues humans. AI won’t revitalise the economy through some invisible hand. It will require visible hands: making it easier to start businesses, harder to entrench monopolies and possible for workers to retrain. We can care about how this happens, and do our best to make it go well.

Teatime scroll Each week I share links to writings, events, tweets and other conversation-starters. If you have something you think should be in here, feel free to email or DM me.

🥼 Big news from DeepMind today, which has signed a deal with the Government to build its first automated research lab in the UK.

🇩🇪 Plans are progressing for a direct high-speed rail link between the UK and Germany. Services could start running between London, Cologne and Frankfurt in the early 2030s.

🧫 The British Business Bank is making the largest investment in its history of $100m into Dame Kate Bingham’s bioscience fund SV8.

📹 For The Guardian, Anna Moore has the inside story on how an unusually swift campaign got deepfake intimate image abuse banned as part of the Data (Use and Access) Act.

🛣️ Anastasia Bektimirova writes about how local authorities in the West Midlands trialed AI tools to improve road safety.

🚴🏼 In the Press Gazette, I wrote about the launch of a new AI-powered cycling news website (as in, the content is AI-assisted, not the cycling), which is the first test case for an automated publishing platform.

💶 Nick Clegg has joined London and Luxembourg VC firm Hiro Capital, which is launching a fund targeting the scale-up capital gap in the UK and Europe.

🏖️ The ICO is considering expanding the Sandbox support it offers organisations who are creating innovative products using personal data. There is a short survey open until 5 January for anyone who wants to give their views.

⚖️ A new report from the Ada Lovelace Institute examines the civil liability of AI and argues that the UK’s current rules aren’t sufficient to address the challenges the technology poses.

🪞 On Monday night, the London AI Hub is hosting a 2025 reflections event with Google and Earlybird.

💬 The Adam Smith Institute has announced another talk in its The Next Generation series for under-35s, this time with Reform Councillor Laila Cunningham. This one isn’t until 13 January but you can register now here.

📚 A new edition of Literary Listings London is out now. I often check this one for talks about tech and politics that might interest readers, but there’s always so much more happening on a range of other topics too. See the newest list here.

👑 And if you didn’t see it yet, please do have a listen to the Sovereign Albion podcast. The first episode is an interview with John Fingleton and Mustafa Latif-Aramesh.

Thank you for featuring Literary Listings London!